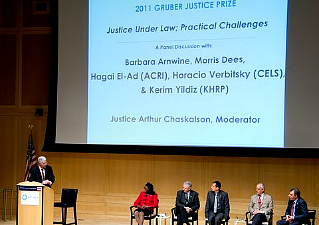

טקס קבלת הפרס (חגי במרכז). צילום: ליבי לנקינסקי פרידלנדר

טקס קבלת הפרס (חגי במרכז). צילום: ליבי לנקינסקי פרידלנדרצפו בנאומו של חגי אלעד, מנכ"ל האגודה

פרס גרובר הבינלאומי לצדק מוענק מדי שנה על ידי קרן פיטר ופטרישיה גרובר לאנשים או ארגונים מרחבי העולם בשל קידום הצדק באמצעות ערכאות משפטיות ושוויון בפני החוק. השנה זכתה בפרס היוקרתי האגודה לזכויות האזרח, יחד עם עוד שני פעילים אמריקאים ושני ארגונים מרחבי העולם.

טקס קבלת הפרס נערך ב-6.10.11 בפילדלפיה. צפו בנאומו של חגי אלעד, מנכ"ל האגודה (הטקסט – בהמשך).

Distinguished guests, members of the Justice Selection Advisory Board and of the Peter and Patricia Gruber Foundation, 2011 prize recipients: I would like to begin by again thanking the Foundation for honoring ACRI, the Association for Civil Rights in Israel, in such a way, and even more so – for the prize to be awarded to ACRI at these challenging times. Your support moved all of us deeply. And, I want to congratulate this year’s co-recipients of the prize. It is an honor for ACRI to be receiving this prize together with such distinguished scholars, activists, and organizations. And I want to extend especially heartfelt congratulations to Horacio and to all our colleagues at CELS – through the International Network of Civil Liberties Organizations we have grown to know and admire your courageous work. Congratulations, and thank you.

The Gruber Prize is given to ACRI first and foremost for our work “in advancing the cause of justice as delivered through the legal system.” But I am no lawyer – actually, I was educated as an astrophysicist, hence the Gruber Cosmology Prize may have been the appropriate venue for me, where amongst geeky scientists I may have found myself in a galaxy more consistent with my background – but, as we are not in that parallel universe, I wanted to explain how it is that ACRI attorneys were so otherwise preoccupied. Well, it happened to be so scheduled, that yesterday the High Court in Jerusalem heard three petitions brought before it by ACRI. From demanding that the court strikes down the anti-democratic Nakba law, to appealing against the practice of racial profiling in security checks in Israel’s airports, to demanding equal representation for Arabs and women on the board of the Israel Land Authority – those are the cases of yesterday’s crop. So you see, our attorneys had very good reasons that kept them away! And while they are not here in person, their work is our inspiration, and their names can be present here with us: Dan Yakir, ACRI’s chief legal counsel, with more than 20 years of unparalleled experience in litigating Israel’s defining human rights cases; Attorney Dana Alexander, the director of ACRI’s legal department; Auni Banna, Limor Yehuda, Tali Nir, Avner Pinchuck, Lila Margalit, Oded Feller, Keren Tsafrir, Gil Gan Mor, Nisreen Alayan, Rawia Aburabia, Maskit Bandel, Nira Shalev, Raghad Jaraisy and Anne Suciu are Israel’s leading human rights legal team. Together with all of ACRI’s staff – educators, campaigners, public advocacy experts, field researchers – we are Israel’s largest and oldest human rights organization, ready to celebrate our 40th anniversary next year.

And while we have much to be proud for, of what we have achieved in almost four decades of steadfast work, I wish that I was able to stand here today proud not only of ACRI, and indeed – proud of the work of our many courageous colleagues in Israel’s human rights family. But I am not proud. As an Israeli citizen, I take responsibility for what is done in my name, by my country. At 39, ACRI is already one of Israel’s oldest civil society organizations. But at 44, the occupation is even older. For millions of Palestinians to be living in a reality of constant human rights violations as a daily norm is an offense of such scale, one does not know where to even begin describing it – and there is no end in sight. It is a shameful reality. The shadow that it casts cannot be turned back at a checkpoint, nor will it be stopped by the separation barrier; it won’t be silenced by a military order, or pushed aside to a road where only people of a certain kind are allowed to travel; this shadow cannot be confiscated, uprooted or dispersed.

It darkens the skies of the Occupied Palestinian Territories – and it clouds Israel’s democracy to a point where one has to ask: if for most of Israel’s history it has controlled millions of people with no civil rights, what regime is that? If what “Jewish and democratic” has come down to is a democracy for the Jews, well to that all justice seeking people must say: that is not democratic, and that is not Jewish. At ACRI, we have fought for years against human rights violations that result from the occupation; many a time, the courts in my country have let us down: they have opened their doors to hear these appeals according to law, but their decisions did not deliver justice. But either way, our goal is not to establish via these appeals an occupation that is more compatible with human rights, because that is a contradiction in terms. For human rights to be respected, the occupation must end. That is our goal. After 44 years of this, and counting, I cannot be proud. I am ashamed.

Of course, there are also other major human rights issues that occupy our mind. The rights of Arab citizens of the State of Israel – on Monday night a mosque in a small Arab village in the Galilee was set on fire, and only a few weeks ago the government approved a plan that if implemented will force the displacement of thousands of Bedouins from their so-called “unrecognized” villages in the Negev – and these are just two examples of decades of institutionalized discrimination. And further issues: the initiative to establish a national biometric database in Israel. The deportation of the children of migrant workers. Abuses against asylum seekers. The erosion of democracy education in schools. Discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual – and especially against transgender Israelis. The usage of secret evidence and administrative measures. Threats to freedom of speech, free assembly and the right to peacefully protest.

Yes, many injustices occupy our minds and our work. But being conscious of time, I would want to now focus and talk about issues that occupy the minds of 99% of the people: social and economic justice. For the dogma that certain economic policies will best serve the greater good of the people has occupied minds, distorted policies, and hijacked politicians for times sufficiently long to push our societies past the point of what people are willing to accept. In that context, as an Israeli, I am proud. Proud not of the fact that the United States and Israel are competing who will lead over the other in international inequality scales – of the developed nations, America currently ranks 4th with Israel a close 5th. But rather, proud of the fact that the movement now emerging in this country emanating from Wall Street, was inspired by the people of Egypt, Spain – and Israel. The hundreds of thousands of Israelis that have demonstrated over the summer for social justice would translate, scaling by population size, to millions of Americans. What were we protesting against? In a country with national health insurance, Israelis protested against the continued privatization and out-of-pocket costs of health, pushing more and more of us away from adequate care; in a country with record low unemployment, we were protesting the fact that so many of those employed remain poor; in a country with a tradition of learning, we protested the erosion of free, quality education; in a country with socialist roots, we protested the fact that the housing assistance budget was cut by more than half over the last decade. To summarize: Israelis too were on to something. That while our country’s economy was, on average, seeming to fair well, we, as individuals or families, were not.

I do not know yet what concrete results will come out of the summer’s protests in Israel, what will come out of an Israeli Summer that was inspired by an Arab Spring. Some things, however, that have transpired over this summer will not be taken back: healthy doubts in economic dogmas; the joy and energy of activism; and a global view of Israeli society as a possible collective that can come together for a just cause, can inspire others, can remind us that democracy is not what we do when we vote once every few years: democracy is what we do the other 99 percent of the time. Essentially, that was also the message of ACRI’s innovative Project Democracy – reminding the public that democracy is not a formal concept, nor is it equivalent to the tyranny of the majority. But rather, that democracy is about safeguarding minority rights as much as it is about free elections. If the people we elected end up not really representing us, how truly free are such elections anyway?

In recent years in Israel, perhaps even more than the public needed to be reminded of these basic attributes of real democracy, it was our elected representatives, the members of the Knesset. Anti-democratic legislation has become a cornerstone of the Knesset’s work, often with the support of both the government as well as the largest opposition party. Legislating measures that further solidify discrimination against Arab citizens, that threaten the ability of human rights organizations such as ACRI to function freely, that desire to curb the authority of the High Court of Justice – these are the main pillars of this anti-democratic wave. We are fighting this rising tide with public advocacy and grassroots demonstrations, legal opinions and if need be – with legal petitions. To no small extent, we have managed to so far limit or delay the damage. But the direction of this process will not be swayed unless, eventually, more Israelis will sincerely choose democracy. Public opinion polls still show that the vast majority of Israelis support democracy over any other form of government. But when one inquires further, the data shows that the democracy supported by so many is one without minority rights, with less freedom of speech, and one in which human rights groups refrain from voicing embarrassing revelations. Is that a democracy?

Clearly, much work remains. That, of course, is no reason to despair. It is reason to get to it, and we have no shortage of vision, motivation – and work ahead of us. To some extent, the Israeli summer can also be understood as a rejection of the season that preceded it, a season that was much about human rights bashing, with such low points as the foreign minister calling human rights groups “terror assistants” and the Knesset deliberating the establishment of inquiry committees into our work. The social justice protests in Israel have pushed all that aside, and that by itself was a surprising and welcome development. But with summer receding, what winds will now prevail? I do hope that what we’ve witnessed will amount to more than mere seasonal changes. We need lasting change. And for that to be, we need to go back to the principles of the universal declaration of human rights: there, humanity speaks for social justice as much as it speaks for civil liberties. There, we commit to the rights of all members of the human family, not only certain members. For the Israeli social justice summer, there is the challenge: not to limit the vision to social justice alone, but be about justice. And justice – well, it cannot be confined to one side of the green line. Making that into reality will be immensely difficult.

To that difficulty, I want to conclude with some words said in December 2009 in Tel Aviv, at the first annual human rights march, which we’ve led on international human rights day:

“I look with apprehension to our future, and think about this place, our common homeland, that is so dear to my heart, that from all its wings we gathered here today. Martin Luther King, who marched at another time and place, said: “In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.” Today, we are neither quiet nor silent, and what we will remember from this day is not the silence of the majority that insists to remain mute, but the voices of our friends, the strength of our humanity, and the endless possibilities that a vision of human rights promises us all.

We live in a new world. Wherever we look, we see hopeful examples of people who braved their differences for a common future of equality…people [who] have made happen what seemed impossible. Why what others have accomplished could not we? It is possible here too. Let us gather together the power of our common voices for the basic principle of human rights for all. Let us continue towards the realization in this land of the vision of human rights – for ourselves, and for all people.”

Thank you very much.