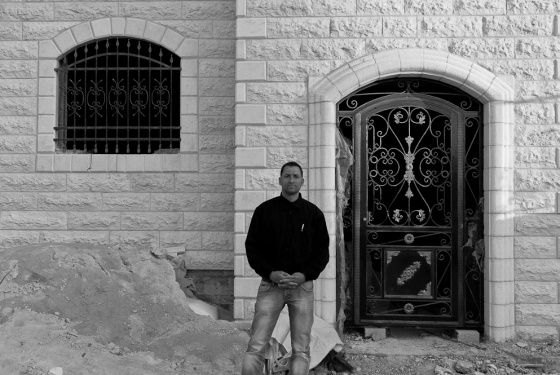

‘3 Houses’ was filmed in the neighborhoods of Jerusalem cut off from the rest of the city by the Separation Barrier. Since construction of the wall began a decade ago, the area has been utterly neglected by the municipality and become a no-man's-land. Now, in addition to the hardships of daily life without police, schools, waste removal, or other basic services, the residents of these neighborhoods must also contend with threats that their homes will be demolished by the city.

A concrete wall over eight meters high separates several Palestinian neighborhoods of Jerusalem from the rest of the city. Tens of thousands of residents live in these areas,[1] which are located within Jerusalem's municipal boundaries.

While the provision of services throughout the Palestinian neighborhoods of Jerusalem is lagging, the situation of the neighborhoods beyond the separation barrier is significantly worse. Despite the responsibility of the Israeli authorities to safeguard the rights of Palestinian Jerusalemites (who are permanent residents of the State of Israel),[2] these areas have been completely neglected since the construction of the separation barrier. There is an acute lack of public facilities such as schools, post offices, and health clinics. There is no police presence, and infrastructure ranges from inadequate to nonexistent, as city workers are loath to enter the area. Standard services such as waste collection, street cleaning, and road repairs have become infrequent or have disappeared completely. Playgrounds, parks and even parking bays have become pipe dreams.

Requests for assistance addressed to municipal departments and government ministries have been ineffective. In July 2012, the media reported Jerusalem Mayor Nir Barkat's intent to request that the military take official responsibility for supplying services to the areas, via the Civil Administration.[3] Steps of this nature indicate to Jerusalem municipal workers that they bear no responsibility for the needs of this area’s residents, whose status as Jerusalemites is often undermined. An absurd situation has come to pass whereby, on the one hand, the Israeli authorities are not providing these neighborhoods with the bare necessities and, on the other hand, the Palestinian Authority is prevented from operating in the area by virtue of the Oslo Accords, which prohibit it from operating within the Jerusalem boundaries.

Threat of home demolitions and lack of planning

For decades, the Israeli authorities have neglected to conduct city planning in these neighborhoods. The lack of an official urban plan makes it impossible for building permits to be issued. In the absence of planning and regulation, construction in these neighborhoods is carried out without permits, and in an unregulated manner. Like mushrooms after the rain, massive buildings have sprung up on every available plot in recent years, leading to the collapse of already weak water and sewage infrastructure.

After a few years of relative quiet, instead of fulfilling its obligation for planning and enabling development in the area, the Jerusalem Municipality renewed its policy of home demolitions. In 2013, the municipality asked the courts to authorize the demolition of dozens of buildings and houses in the Ras Khamis and Ras Shehada neighborhoods, affecting hundreds of families.[4] The municipality also began to map unlicensed construction in the area which is likely result in additional demolition orders.

A water crisis

In March 2014, water supplies were cut off almost completely in the homes of tens of thousands of residents living in Ras Khamis, Ras Shehada, Dahiyat a-Salam and the Shuafat Refugee camp. Families were forced to purchase water and to significantly reduce water consumption for cleaning, drinking, and other daily activities. In response to an urgent petition to the High Court of Justice submitted by ACRI on behalf of the residents,[5] the Hagihon water utility, which provides water and sewage treatment in Jerusalem, admitted that the water infrastructure of the area can support some 15,000 residents, and that they estimate approximately 60,000-80,000 people reside in these four neighborhoods. In June the State asked the court for an additional 90 days to further examine the problems of water connection and its possible solutions.

Daily passage through checkpoints

The residents of the neighborhoods beyond the separation barrier are intimately connected to Jerusalem. As in the past - before the construction of the barrier - they must reach the rest of the city for work, study, family visits and to access healthcare and other services. Tens of thousands of people are forced to cross daily through a checkpoint on their way to other parts of the city.

The Jerusalem residents of Kfar Aqab and Samiramis cross through the Qalandiya Checkpoint, which is also used by thousands of residents of the Palestinian territories who hold entry permits into Israel. The checkpoint and the roads that lead to it are renowned for the massive traffic jams that take place every day of the week, and those crossing are forced to contend with overcrowding and long wait-times. Residents of the Shuafat refugee camp and the surrounding neighborhoods of Ras Khamis, Ras Shehada and Dahiyat a-Salam cross through the Shuafat Refugee Camp Checkpoint, which is designated for use only by residents of the area who hold Israeli identity cards (i.e. not residents of the West Bank).

Only a few years ago, the High Court of Justice approved the route of the separation barrier through the area on the condition that the state ensure that the normal routine of residents would continue in spite of the wall and the checkpoints.[6] In practice, these promises have gone unfulfilled.

[1] The exact number of residents in these areas is unknown. According to estimates published in March 2011 by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the number of residents in these areas is as many as 55,000 (East Jerusalem: Key Humanitarian Concerns. United Nations – Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, pp. 68-69) http://www.ochaopt.org/documents/ocha_opt_jerusalem_report_2011_03_23_web_english.pdf. According to the Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies' 2013 Statistical Yearbook, 35,000 Palestinians who hold Israeli identity documents live in Jerusalem neighborhoods beyond the separation barrier (Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, The Statistical Yearbook for Jerusalem 2013 edition, Population of Jerusalem, by Age, Quarter, Sub-Quarter and Statistical Area, http://jiis.org.il/.upload/yearbook2013/shnaton_C1413.pdf). Other estimates, which include both Palestinian holders of Israeli IDs and Palestinian holders of PA IDs, approach 100,000 residents.

[2] Residents of East Jerusalem hold Israeli IDs. The majority of them are considered permanent residents of Israel, while a minority are citizens.

[3] Chaim Levinson and Nir Hasson, Jerusalem municipality asks IDF to take responsibility for residents who live east of the separation fence, Haaretz, 24 July 2012, http://www.haaretz.com/news/diplomacy-defense/jerusalem-municipality-asks-idf-to-take-responsibility-for-residents-who-live-east-of-the-separation-fence-1.453149.

See also ACRI’s appeal to Jerusalem Mayor Barkat, 26 July 2012, https://law.acri.org.il/he/?p=22979 [Hebrew].

TechnoCraft

TechnoCraft